I watched the Indianapolis 500 this Memorial Day weekend and noticed something interesting. The fastest car completed 4 qualifying laps around the 2.5-mile oval with an average speed of 227 mph. However, the average speed of the winning car was a meager 162 mph. That is a big difference when you consider the conditions were, to the passive observer, similar. But a closer look reveals the underlying realities.

During qualifying, there is only one car on the track, you have brand new tires, and there is only enough gas in the tank to go 10 miles. During the race, tires are worn, there are 32 additional cars on the track, and the gas tank is full of fuel. While the components are the same, the conditions in which they exist are very different.

The same is true for pharmaceutical marketers. We position medications in the real world using data collected from the idyllic world of clinical trials. Yet, we are often caught flat-footed when safety signals begin to emerge after a drug has been on the market. The question is, why are we constantly surprised? The answer is, we shouldn’t be, and we need to be better prepared when it happens.

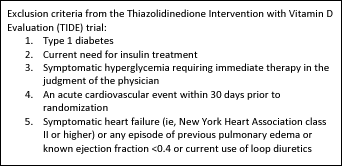

Just like the Indianapolis 500, in a clinical trial, not everyone who participates in the qualifier gets to race. For example, the TIDE trial is investigating “the cardiovascular effects of long-term treatment with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone when used as part of standard of care compared to similar standard of care without rosiglitazone or pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who have a history of or are at risk for cardiovascular disease.” A brief look at the first five exclusion criteria for this trial demonstrates that the average trial subject is very different from the average patient with T2DM.

This could explain why some patients respond well to a treatment and others do not; however, should it also influence the decision making process?

Pharma marketers need to be adequately prepared if/when questions like these arise. One way to accomplish this is for us to engage in therapeutic “war games” where different scenarios and outcomes are modeled under the guidance of a practicing physician. For the sales force, exercises like this would be very beneficial if they must answer questions or criticisms from healthcare professionals. Many of our colleagues often scramble for the appropriate response when something like this happens. Our mandate is to change our way of thinking from reactive to proactive to respond better to these eventualities.

RELATED TOPICS

Ken is a great deal more than just the president of a medical communications company. He is something of a hybrid. He’s part marketing manager, part creative director, and part copywriter. To the chagrin of his peers—but to the delight of his clients—Ken is a consummate perfectionist. As a former creative director for a high-end consumer agency, he challenged his creative teams to go beyond the mundane to produce work with real creative impact, something he’s just as fervent about today. From producing and directing TV commercials, to launching DTC and Rx-to-OTC switches, Ken brings his clients a world of experience in OTC pharmaceuticals as well as business, lifestyle, and high-end consumer products and services. Whether huddled with clients behind a mirror in a market research center in Houston, facilitating a strategic workshop in Madrid, or developing a global campaign either in the New Jersey or California office, Ken is always fully engaged, bringing “bestness” to all areas of his hectic but full life.